|

"What's better, low

compression and more boost or high compression and less boost?"

There

are certainly reasons to try to raise compression ratio, namely when

off-boost performance matters, like on a stree tcar, or when using a

very small displacement motor. But when talking purely about on-boost

power potential, compression just doesn't make any sense.

People

have tested the power effects of raising compression for decades, and

the most optimistic results are about 3% more power with an additional

point of compression (going from 9:1 to 10:1, for example). All

combinations will be limited by detonation at some boost and timing

threshold, regardless of the fuel used. The decrease in compression

allows you to run more boost, which introduces more oxygen into the

cylinder. Raising the boost from 14psi to 15psi (just a 1psi increase)

adds an additional 3.4% of oxygen. So right there, you are already past

the break-even mark of losing a point of compression. And obviously,

lowering the compression a full point allows you to run much more than

1 additional psi of boost. In other words, you always pick up more

power by adding boost and lowering compression, because power potential

is based primarily on your ability to burn fuel, and that is directly

proportional to the amount of oxygen that you have in the cylinder.

Raising compression doesn't change the amount of oxygen/fuel in the

cylinder; it just squeezes it a bit more.

So

the big question becomes, how much boost do we gain for X amount of

compression? The best method we have found is to calculate the

effective compression ratio (ECR) with boost. The problem is that most

people use an incorrect formula that says that 14.7psi of boost on a

8.5:1 motor is a 17:1 ECR. So how in the world do people get away with

this combination on pump gas? You can't even idle down the street on

pump gas on a true 17:1 compression motor. Here's the real formula to

use:

sqrt((boost+14.7)/14.7) * CR = ECR

sqrt = square root

boost = psi of boost

CR = static compression ratio of the

motor

ECR = effective compression ratio

So

our above example gives an ECR of 12.0:1. This makes perfect sense,

because 12:1 is considered to be the max safe limit with aluminum heads

on pump gas, and 15psi is about as much boost as you can safely run

before you at least start losing a significant amount of timing to

knock. Of course every motor is different, and no formula is going to

be perfect for all combinations, but this one is vastly better than the

standard formula (which leaves out the square root).

So

now we can target a certain ECR, say 12.0:1. We see that at 8.5:1 CR we

can run 14.7psi of boost. But at 7.5:1 we can run 23psi of boost (and

still maintain the 12.0:1 ECR). We only gave up 1 point of compression

(3% max power) and yet we gained 28% more oxygen (28% more power

potential). Suddenly it's quite obvious why top fuel is running 5:1

compression, that's where all the power is!!

8.5:1

turns out to be a real good all around number for on and off boost

performance. Many "performance" NA motors are only 9.0:1 so we're not

far off of that, and yet we're low enough to run 30+ psi without

problems (provided that a proper fuel is used).

Example: "I've got a 500+ CID motor and

I'm looking to make 900hp. Can I use a GT42, I've heard they can make

900hp?"

Nope!

There's nothing wrong with the GT42, it will definitely make 900hp,

just not in this scenario. Here's why: 900hp represents a fairly

constant amount of air/fuel mixture, regardless of whether it's being

made by a small motor at high boost (e.g. 183ci at 32psi) or a large

motor at low boost (e.g. 502ci at 10psi).

The

first problem is that most compressors are only able to reach their

maximum airflow when they are running at high boost levels. For

example, a GT42 is able to flow about 94lbs/min of air at 32psi of

boost, but it can only flow around 64lbs/min of air at 10psi. Often

people are quick to assume that high boost means high heat and

therefore decreased efficiency, but in reality, it takes higher boost

levels to put most turbos into their "sweet spot". In this particular

example, the turbo is capable of almost 50% more HP at high boost

levels than it is at low boost levels.

The

other problem is related to backpressure. If the exhaust system

(headers, turbine, downpipe, etc.) is the same between both motors, the

backpressure will be roughly the same. Let's say the backpressure

measures at 48psi between the motor and turbine. The big motor will run

into a bottleneck because there is 48psi in the exhaust and only 10psi

in the intake (a 4.8:1 ratio). This keeps the cylinder from

scavenging/filling fully and therefore limits power. The small motor,

on the other hand, has 32psi of boost (only a 1.5:1 ratio) to push

against the backpressure. Therefore it is able to be much more

efficient under these conditions.

The

bottom line is, as your motor size increases, your boost level will go

down (in order to achieve the same power level). In such a case you

will need to maximize the flow potential of your compressor and

minimize the restriction of your exhaust system (including the turbine)

in order to reach your power goals.

FINAL COMPRESSION RATIO

CHART

This

chart shows the final compression ratio in your engine by combining the

static compression ratio read down the left side and the amount of

boost applied to the engine across the top. Use this chart shown below

as a guideline to determine the proper amount of maximum boost level

for a specific application.

Final

compression ratios above 12.4 to 1 are not recommended for use with

"premium pump gasoline." The higher the final compression ratio the

higher the octane rating of the gasoline must be in order to help

prevent detonation and serious engine damage.

Final Compression Ratio (FCR) = [(Boost/

14.7) +1] x CR

boost = psi of boost

CR = static compression ratio of the

motor

FCR = final compression ratio

Altitude

plays an important role in determining compression ratios. If the

altitude in the area where the vehicle is driven is significantly

higher than sea level then the compression ratios will vary. To

determine the effects of the altitude on a calculated compression ratio

use the following formula:

Correct Compression Ratio = FCR

minus [(altitude/1000) x 0.2]

| Compression |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Ratio |

|

|

|

|

Boost (in

pounds per square inch) |

|

|

| |

2

|

4

|

6

|

8

|

10

|

12

|

14

|

16

|

18

|

20

|

22

|

24

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 6.5:1 |

7.4 |

8.3 |

9.2 |

10.0 |

10.9 |

11.8 |

12.7 |

13.6 |

14.5 |

15.3 |

16.2 |

17.0 |

| 7.0:1 |

8.0 |

8.9 |

9.9 |

10.8 |

11.8 |

12.7 |

13.6 |

14.5 |

15.3 |

16.2 |

17.0 |

17.9 |

| 7.5:1 |

8.5 |

9.5 |

10.6 |

11.6 |

12.6 |

13.6 |

14.6 |

15.7 |

16.7 |

17.8 |

18.6 |

19.5 |

| 8.0:1 |

9.1 |

10.2 |

11.3 |

12.4 |

13.4 |

14.5 |

15.6 |

16.7 |

17.8 |

18.9 |

19.8 |

20.9 |

| 8.5:1 |

9.7 |

10.8 |

12.0 |

13.1 |

14.3 |

15.4 |

16.6 |

17.8 |

18.9 |

19.8 |

20.9 |

21.9 |

| 9.0:1 |

10.2 |

11.4 |

12.7 |

13.9 |

15.1 |

16.3 |

17.6 |

18.8 |

20.0 |

21.2 |

22.4 |

23.6 |

| 9.5:1 |

10.8 |

12.1 |

13.4 |

14.7 |

16.0 |

17.3 |

18.5 |

19.8 |

21.1 |

22.4 |

23.6 |

24.8 |

| 10.0:1 |

11.4 |

12.7 |

14.1 |

15.4 |

16.8 |

18.2 |

19.5 |

20.9 |

22.2 |

23.6 |

24.8 |

26.0 |

| 10.5:1 |

11.9 |

13.4 |

14.8 |

16.2 |

17.6 |

19.1 |

20.5 |

21.9 |

23.4 |

24.8 |

26.2 |

27.6 |

| 11.0:1 |

12.5 |

14.0 |

15.5 |

17.0 |

18.5 |

20.0 |

21.5 |

22.9 |

24.5 |

26.0 |

27.5 |

28.9 |

|

Engine compression ratio

- how does it affect performance and economy?

In

an internal combustion engine, a piston compresses a large volume of a

mixture of fuel and air into a very small space. The ratio of the

maximum piston volume to the minimum compressed volume is called the

"compression ratio."

Compressing

the fuel and air will make them burn faster, which (though I'm not sure

directly how) makes the engine run better. Due to the high compression

ratio (12.51) of the 11,000 RPM Hayabusa engine and the low compression

ratio (9.8:1) of the 6500rpm Mustang V8, I'm guessing that this allows

for a much higher redline - the faster burn speed of the compressed

fuel-air mix in the Hayabusa engine would allow it to complete burning

before the piston had completed its stroke at high RPMs.

There

are secondary benefits to high compression ratios, too. High

compression ratio engines burn both much more cleanly and much more

efficiently than lower-compression engines. For example, a diesel

engine, which burns fuel very differently to a gasoline engine, will

often give fuel economy 60% greater than its gas equivalent, even

though diesel only has about 10% more energy per gallon.

According

to Wikipedia, the increase in efficiency is due to the additional heat

and brownian motion caused by compression fully vaporizing the fuel,

which I think sounds a little fishy considering how much work is put

into cooling the fuel-air mix in turbocharged cars. Most other websites

say that it's due to the Carnot cycle, which I honestly do not

understand - could someone explain it?

Another

issue is engine efficiency as a function of RPMs. An engine limits

power by reducing the intake of fuel and air to an engine; if only half

the fuel and air is entering a piston, the compression ratio is

effectively halved as well.

Considering

all the advantages of high compression, one might wonder why anyone

would not use a high compression ratio. The answer is simple: The

increased heat density of the compressed gas will cause the fuel to

begin combustion without ignition by the spark plug, resulting in an

undesirable burn pattern. This detonation, or "knock", is often heard

as a pinging noise and can cause severe damage to your engine.

The

measure of a fuel's minimum ignition temperature and resistance to

detonation is its octane, which is not, as is commonly understood, a

measure of it's energy per liter. Before the advent of the catalytic

cracker, fuel was often below seventy octane, and engine compression

ratios were low - a Model T had a compression ratio of 4.5 to 1.

However, by splitting large molecules into smaller ones (cracking),

modern engines are both more efficient and better performing than their

older brethren.

Modern

gas has an octane of about 93 for premium in the US, and about 97 in

the rest of the world. 100+ octane gas can be had, but it's very

expensive (well over $5/gallon) and often has octane-boosting additives

which contain lead. However, all of these are dwarfed by ethanol, which

as an octane rating of a whopping 129. As a result, it can easily be

used in engines with a compression ratio of 15:1 or greater, and

despite having an energy density only 2/3 that of gasoline, it should

produce similar fuel economy in such an ethanol-optimized engines along

with very, very high redlines.

Running

higher compression ratios is a very hotly debated subject at the moment

and the two camps are extremely divided. As a lot of you probably know,

the two “camps” consist of the old school Cosworth era tuners who have

been building engines with lowered ratio’s for years (and have worked

well) and the newer breed of tuners (mainly stemming from USDM Honda

scene) who have had great practical and proven success building higher

compression turbo engines.

Let’s start with the

correct turbo choice for your application.

People

run smaller turbo’s because they want them to spool early and to

deliver a wider range of power. Turbo A (smaller turbo) running 1.0bar

will spool faster than Turbo B (slightly larger) running the same boost

pressure, but the amount of air moved by Turbo B (slightly larger) will

be greater at the given boost pressure as it’s moving more air? Thus

creating more power.

The

problem is that the more boost pressure you run, the more the charge is

heated by the turbo. This results in the temperature of the air/fuel

mix entering the combustion chamber to be significantly higher. Once

the piston is on it’s up stroke, this air and fuel mix is compressed

and something called adiabatic heating occurs. (*which is the increase

in temperature of a fluid when under pressure) if this air fuel mix

reaches the auto-ignition point of gasoline you get premature

detonation or det (The air/fuel mix auto igniting before the spark plug

fires – not like premature ejaculation).

By

upping the compression ratio in an engine, your increasing the heat

that is generated when the gas is compressed on the upstroke (but also

increasing the density of the gas/air mix and extracting more

mechanical energy) this means that your inlet temperatures and fuel

octane are significantly more important. Higher octane fuel has a

higher auto ignition temperature and is more difficult to burn (the

opposite to common belief that high octane fuel is actually more easily

ignited) thus making your combustion process more det resistant.

The

type of piston and shape of the combustion chamber, determines the

speed of the flame front that travels across the compressed mixture.

In

simple terms a higher compression ratio DOES create more power off

boost which gives you extra torque down the arse end. It’s really down

to static vs. effective compression.

Effective

compression is the sum of the static compression, plus the additional

compression added to the cylinder by a turbo or super charger, or any

other forced induction tool for that matter. Effective compression is

defined by the following formula:

E = C((B / 14.7) + 1)

Where E= Effective Compression, B= boost

psi, and C= Static compression. Also remember that 14.7 is equal to 1

bar of boost.

Let’s do an example. Let’s say we have a SR20DE bone stock with 10.4:1

static compression and slapped on a turbo kit. It’s now boosting 7psi.

That takes care of our variables. Let’s do the math.

E = C((B / 14.7) + 1)

E = 10.4((7 / 14.7) + 1)

E = 10.4((.476xx) + 1)

E = 10.4(1.476xx)

E = 15.35xxx

As

you can see, we come up with an effective compression ratio of 15.3 or

so. A motor in this effective compression range is easily daily driven

with proper fuel and timing adjustments/upgrades.

(Running on the same turbo back

to back)

If you’re running a 9.0:1 compression

ratio @ 1 bar you’ll achieve an effective compression ratio of 18:1

If you’re running a 7.5:1 static

compression ratio and 1 bar of boost you achieve an effective

compression ratio of 15:1.

For

the 7.5:1 to reach the same effective compression ratio you need to run

.4bar or 5psi more boost. Combined with the fact that you have less

“grunt” outside the boost threshold. Less grunt/torque means your

engine produces LESS of a bang when the combustion mixture ignites,

along with a slower burn due to a less compressed cooler mixture.

So

in a nutshell – if you’re running 2.0 bar of boost on a 7.5:1 static

ratio your achieving an effective compression ratio of 22.5:1 if you

run the same setup with 9.0:1 static ratio you get the same effective

compression ratio but with only 1.5 bar of boost and much better

drivability outside of the boost threshold and a better spool due as a

result.

Of

Course, if the compression ratio is too high then the adiabatic effect

will cause the mixture to auto ignite – so there is a line to be drawn

obviously.

When

building turbo engines static compression ratio is actually a bit of a

clumsy way of measuring what’s going on because your measuring the C/R

at atmospheric pressure not the desired. With that said, a higher C/R

engine will produce more power off boost and subsequently spool your

turbo slightly faster. You need to aim for a power goal (whatever that

is) and spec your turbo setup accordingly to produce the required air

at a reasonable pressure & temperature.

ALCOHOL FUELS

RIGHT

at this point it might be as well to point out to readers that the

handling of alcohol fuel, even in small quantities, is dangerous since

poisonous Methyl Alcohol is the basis of most of these fuels.

In

some cases to prevent it being used for drinking an additive is used,

called Pyridine, about one half per cent being the amount.

This gives it a nasty smell and a vile

taste, but pure fuel is, of course, without this deterrent.

The

problem still remains, however, since it can get into the system by

absorption through the skin or cuts, and can be inhaled from exhaust

gases.

The effects are cumulative and if enough

build up is allowed it oxidizes forming Formaldehyde causing blindness

and insanity.

The

use of rubber gloves, avoiding splashing and handling in confined space

and in general treating with commonsense, however, reduces the risks to

acceptable proportions.

Should, however, any get in the eyes

immediate medical attention is necessary.

For

those who have not handled alcohol fuel it might be as well to say it

is a clear, colorless liquid, cool in touch, with an odor different

from petrol, and has an attraction to moisture in the atmosphere.

ADVANTAGES AND

DISADVANTAGES

Let

us now investigate the advantages and disadvantages of going over to

this fuel, and at all times taking petrol as our reference level,

having in mind the basic requirements of fuel in the heat engine.

The

first question must be is it easy to obtain and the answer is there are

a number of garages retailing the fuel, in certain cases with other

fuels added in specified quantities.

Having obtained the fuel, as already

explained, it must be handled with care and commonsense.

There

is no real problem in keeping in store any quantity left over from one

meeting to another, provided it is kept in a can, or tank for that

matter, with the cap kept on during the store period, which can extend

into years, contrary to popular belief.

COST

Cost

of the alcohol depends on what other fuels have been incorporated, but

as guide pure alcohol is, in small quantities, about just over half as

much again as the cost of top grade petrol. You must bear in mind at

this point, however, you will require double the amount of alcohol as

compared to petrol for reasons which will be explained later.

Another

point to consider is that alcohol is a solvent and so far as certain

paints are concerned it acts as a perfect paint stripper. Alcohol also

has a very thorough scouring effect on tanks, pipe lines and so on, not

forgetting it can on certain

types of fiberglass tanks cause them to

disintegrate into a rather nasty sticky mess.

CONSUMPTION

Consumption

of alcohol will be, in rough figures, double that of petrol, due to the

calorific value being about half that of petrol.

The

correct air-fuel ratio for petrol is 14.1 to 15.1, but for alcohol it

is 7.1 to 9.1 so that means we must pass at least twice the weight of

fuel, in the case of alcohol, to heat the same amount of air to the

same temperature as we need for petrol.

Since

the specific gravity of the two fuels is near enough the same it means

in effect we have to pass through the jets double the quantity of the

fuel.

Apart from doubling up the flow capacity

of the jets, and we would add here that this does not mean doubling up

the diameter of

the jet hole as many people think, but, in fact, increasing the

diameter by 1.4 times or if you like by 40 per cent since a little

thought will remind you of the fact you are dealing with the area of

the hole in the jet and not the diameter.

It

is of little use increasing the capacity of the jet to pass double the

amount of fuel unless steps have been taken to establish that the fuel

lines, taps, float chambers and so on are also capable of passing

double the fuel and the actual flow should be measured.

RICH SIDE

Now

unlike petrol you will find alcohol fuel will continue to provide

increased power for a mixture well above the ideal mixture strength and

you can always tend, therefore, to jet up on the rich side, and so

avoid any possible chance of running into troubles through weak mixture

causing burnt valves and holed pistons.

This

larger amount of fuel compared to petrol and especially as it is a fuel

with much higher latent heat value tends to do two things. The density

of the charge entering the engine is higher than petrol and a greater

weight of mixture is therefore being exploded.

This

is a fuel with a large cooling effect provided by part of it

evaporating after it has reached the combustion chamber and so tending

to cool the valves, piston and so on.

Some

may well get into the combustion chamber as liquid, due to the

reduction in temperature of the induction system, pipes, carburetor,

etc., and so extending the cooling effect, in the process counteracting

the effect of the high internal temperature.

In

view of this amount of fuel entering the chamber, with possibly some of

it in liquid form, the ignition system must be beyond reproach since if

the spark is weak the mass of fuel will just soak the plug and then at

once ignition troubles arise affecting starting in particular.

Owing

to the use of alcohol a higher compression ratio can be used with this

fuel as compared with petrol, another consideration is the type of plug

used which will be a hotter type than used before with petrol.

NINETEEN TO ONE

We

have just mentioned the higher possible compression ratio used with

alcohol and the limit that can be used with any particular fuel depends

on the tendency of the fuel to detonate.

As

a rough guide the ratio for petrol is limited to about ten to one, or

with certain additives to as much as 12 to one. With alcohol, however,

you can go up to 19 to one or higher in certain cases. (For all

practical purposes however, 14 to one should be considered the maximum

usable ratio in modern short stroke automotive engines.)

The

possible use of a much higher ratio, of course, means we get a higher

power output from the engine, and this, in fact, is almost the main

advantage of alcohol fuel.

DETONATION

Detonation

with alcohol fuel is really not a problem, but pre-ignition is, or

could be unless the mixture is kept well on the rich side.

The

reason for this is that if the mixture is on the weak side it burns

slowly and can still be so doing when the exhaust valve has opened

which then becomes overheated. This in turn ignites the next charge

before the correct time, the whole process becoming a chain reaction

causing even more rise in temperature and so it goes on until the

piston holes and other damage then follows.

The

first signs of this process taking place are a loss of power, a general

rise quite quickly of overall temperature, the head in particular.

To avoid this, run on the rich side

always and use plugs with a good heat capacity.

It

might be worth mentioning at this point that an engine set up correctly

for running on alcohol, even though on a rich mixture, will be found to

be (compared to petrol), a much cleaner running engine inside the

cylinder head, and provided the ignition side is up to its job there

will be less fouling of plugs than on petrol.

IGNITION SETTING

Due to the different rate of burning of

alcohol compared to petrol the ignition setting will have to be changed.

It will have to be advanced and the

amount necessary will depend on the shape of the cylinder head and

general design.

For

example, on a well designed hemi-head an extra five to six degrees

might well be enough, whereas on a poor designed head it might be

something like 15 degrees.

Optimum

ignition setting is tied up with the air-fuel ratio and it will be

found that with alcohol it is not so critical as with petrol, that is

to say the drop off of power is not so progressive as will be seen

later.

STARTING

Provided

the engine is set up for running on alcohol correctly there should be

little trouble in starting except perhaps on a very cold day and it

should be possible to start up on the fuel mix used for the actual

racing.

The

main problem, due to the cooling effect of the fuel, is to get the

engine to operating temperature in the short time available from

fire-up to staging.

For this reason so far as motor cycle

type engines are concerned, you will note,

in

many cases, the finning on the cylinder barrels and heads is almost

eliminated. This, by the way, also helps to increase the power to

weight ratio, or if you like tends to counteract the weight of the

extra amount of fuel carried as compared to petrol.

LIMIT

From

reading this far, you should have come to the conclusion that if your

engine is now on its limit running on petrol, while large increases of

power are obtainable by the use of higher compression ratios it is

possible to get a reasonable increase in power output, ten per cent or

so, with the existing ratio, provided you make quite certain you get

enough fuel through to the engine and, in fact, that you tend to run on

the rich side.

Once

you have gone over to alcohol and obtained satisfactory running, you

have commenced an extension of your power output by anything up to 25

per cent as you adapt the engine to run with the new fuel.

The

rather attractive feature that you tend, even with the increase of

power to stand less chance of doing damage to the engine than when on

petrol should also be considered.

FINAL POINT

One

final point to consider. If you change over to alcohol from petrol

where you were using a mineral oil, it is not necessary to change over

to a castor based oil. For modern engines, the present type additive

mineral oils offer a higher performance level than the additive castor

based oils, and under controlled conditions the light viscosity oils

have an advantage where the warm up time is limited.

BASIC FUEL CHARACTERISTICS

|

GENERAL

DESCRIPTION

METHANOL (Methyl Alcohol)

CH30H is a volatile, highly inflammable, water-clear liquid with a

mildly spirituous odor Miscible with water or nitromethane in all

proportions and almost all with petrol.

|

BASIC

CHARACTERISTICS

|

Flash Point

|

Boiling Point

|

Freezing Point

|

Specific Gravity

|

Lbs/Gall approx

|

|

F C

|

F C

|

F C

|

|

|

61 16 148 64 -144 -97 0.796 8

|

NITROMETHANE

CH3NO2

is an inflammable water-clear liquid with a mild odor, containing

approximately 53% by weight of oxygen. Water will mix with nitromethane

to the extent of 2.5% only, by volume. |

110 43 214 101 -20 -29 1.13 11.25

|

ACETONE (Dimethyl

Ketone) CH3COCH3

is a highly volatile, highly inflammable, water-clear liquid with a

strong, sharp, characteristic odor. Miscible with all the chemicals

listed here, and water. |

0 -18 133 56 -138 -94 0.791 8

|

ETHER

(Diethyl Ether) C2H5OC2H5

is an extremely volatile, highly inflammable, water clear liquid with a

strong, lingering, characteristic odor. Miscible with all the chemicals

listed here but not with water. |

-40 -40 95 35 -183 -116 0.714 7

|

BENZOLE,

(Benzene) C6H6

is an inflammable water-clear liquid with a dull sweet odor Miscible in

most proportions with all the chemicals listed here but not with water. |

12 -11 176 80 41 5 0.879 8.75

|

NITROBENZENE

C6H5NO2

is an inflammable, yellow, oily liquid with a strong odor of almonds.

Miscible in most proportions with all the chemicals listed here but not

with water. |

190 88 412 211 41 5 1.20 12

|

PROPYLENE

OXIDE (1 :2. Epoxypropane) CH3-CH-CH2

is an extremely volatile, very reactive, highly inflammable,

water-clear liquid with a light gaseous odor. Miscible with all the

chemicals listed here but only partially with water. |

32 0 93 34 -155 -104 0.83 8.25

|

UCON

LB625 (Polyalkalene glycol)

A water-clear synthetic lubricating oil with exceptionally high film

strength properties. Miscible with all the chemicals listed here but

not with water. |

430 221 - - -25 - 32 1.0 10

|

|

|

|

Conservative

Maximum Compression Ratio

|

Air/Fuel

Ratio for Max Power lbs/lbs

|

Energy from

Combustion B.T.U/lb

|

Cooling

Effect (Latent heat of Vaporization) B.T.U./lb

|

|

Use in Internal

Combustion Engines

|

|

Methanol

|

|

Methanol

permits the use of very high compression ratios when unsupercharged or

high boost pressures when supercharged. The large cooling effect

increases volumetric efficiency and is of particular use in the

supercharged engine reducing charge temperature after compression. A

tendency to pre-ignition is most noticeable at weak mixture levels. |

| Nitromethane |

|

6.5 : 1

(10 : 1 with rich mixtures)

|

2.5 : 1 to

0.5:1 at least

|

5000

|

258

|

|

Nitromethane

enables considerable power increases to be obtained (70 percent minimum

with proper use). Most often used blended with methanol, in various

propor ,tions to provide power increases consistent with engine

strength, etc. A tendency to detonation is reduced by an increase in

mixture strength, reduction in engine temperature, reduction in

compression ratio or the addition of methanol. |

|

Acetone

|

17 : 1 9.4 : 1 12,500 225

approx

|

As

a basic fuel acetone appears to have all the required characteristics,

these in general Iying midway between methanol and petroleum. An

exception is its very high anti-knock rating which approaches that of

methanol. Other uses are as an additive to other fuels, notably to

methanol to reduce pre-ignition sensitivity and promote easier starting

under low temperature conditions, up to 10 percent for this purpose. |

|

Ether

|

|

Not

used as a basic fuel in spark ignition engines due to its very low

knock-rating, but this characteristic is desirable in the small

high-speed diesel engine where it is used in relatively large

percentages (approx. 15 percent to 35 percent by volume) as an

additive. Its volatile nature and low flash point make it useful as an

additive tuP to 5 percent) to improve starting and give a rapid

throttle response. |

|

Benzole

|

15 : 1 10.8 : 1 17,300 153

|

Most

often used blended with methanol to give a greater energy per unit

volume with reduction in the latent heat vaporization, this being a

compromise often used for long distance racing where fuels other than

petrol are allowed. |

|

Nitrobenzene

|

not known 8 : 1 10,800 143

|

Blended

in very small proportions with other fuels it is thought to act as an

ignition accelerator. As this material has a strong odor even after

combustion it is sometimes used as an additive in other fuels (approx.

0.5 percent) to mask the normal exhaust odor making it difficult to

detect the base fuel type. |

|

Propylene Oxide

|

not known 9.6 : 1 14,000 220

|

Used

as an ignition accelerator additive particularly with nitromethane (up

to 20 percent by volume with pure nitromethane) where noticeable

increases in power are possible. Easier starting and smoother running

are other benefits when blended with most other fuels (up to 5 percent) |

|

Ucon

|

At 0 F this oil

compares to SAE 20 at the same temperature, and at 210 F it compares to

SAE 50 at the same temperature |

Used

to advantage in all two stroke engines operating on fuel/oil mixtures.

The unusually high him strength properties allowing a reduction in the

amount of oil in the fuel by as much as 55 percent. Of particular use

in very small high speed two stroke engines where the normal oil

content can be up to 30 percent of the total volume, with the attendant

restriction on the amount oF fuel that can be burnt. |

NOTES

|

Methanol

|

Corrosion

- Magnesium: Attacked.

- Tin: White deposit (long term).

- Polythene: Cracks (long term).

- Paints: Most attacked severely.

- Perspex: Attacked.

|

Handling

Poisonous; do not allow to come

into contact with skin as repeated absorption may have long term

effects on health.

|

| Nitromethane |

- Copper/Alloys: May be attacked.

- Polythene: Generally resistant.

- Paints: Most attacked severely.

- Perspex: Attacked.

|

Do not allow

to come into contact with caustic soda, amines or hydrazine. Pipeline

pressures must be kept below 100-lb/sqlin. |

|

Acetone

|

- Metals: Resistant.

- Polythene: Cracks (long term).

- Paints: Most attacked severely.

- Perspex: Attacked.

- Neoprene: Some attack.

|

Low flash

point presents considerable fire risk. Extinguish with dry powder or

CO2. |

|

Ether

|

- Metals: Resistant.

- Polythene: Cracks (long term).

- Paints: Most attacked severely.

- Perspex: Attacked.

- Neoprene: Some attack.

|

Very low flash

point presents serious fire and explosion risks. Vapor is heavier. than

air and anesthetic. |

|

Benzole

|

- Metals: Resistant.

- Polythene: Generally resistant.

- Paints: Some attacked.

- Perspex: Some attack.

|

Poisonous;

strong vapors must not be inhaled, may affect blood tissues permanently. |

|

Nitrobenzene

|

As for benzole

|

Very

poisonous; do not allow to come into contact with skin or inhale vapors. |

|

Propylene Oxide

|

- Metals: Most resistant.

- Polythene: Cracks (long term).

- Paints: Most attacked severely.

- Perspex: Attacked.

- Neoprene: Some attack.

|

A very

reactive chemical, must not be allowed to come into contact with

copper/alloys or rust, reaction may be violent. |

|

Ucon

|

No problems

|

No problems

|

Alcohol Problems

For the racer there seem to be many positives for using alcohol as a

fuel; are there any downsides? Yes, there are a number of issues that

alcohol brings to the party that are not even considerations with

gasoline fuels. The first is that alcohol is hygroscopic. It will

absorb water out of the air if it’s exposed to the environment. This

little feature can make a perfectly acceptable jug of fuel not worth

using if the water content gets too high. This feature of alky fuels

is, and has been, the bane of many tuners as they make changes to the

fuel system only to find that the fuel was contaminated with water.

This

is also a real problem in areas that have a good bit of humidity in the

air. In the Southwest it’s not a big issue but it still means that any

alcohol that is stored needs to be in containers that are not vented

and that the fuel should not be exposed to the environment any longer

than possible.

Another downside is that many

of the rubber type seals that are used in gasoline fueled cars don’t

hold up when the fuel is changed to alcohol. They don’t react well with

alcohol fuels, often degrading and no longer offering an acceptable

seal, or even worse they degrade and contaminate the fuel downstream of

their location. While this seems like a real issue, it’s simply

rectified, by using seal materials that are resistant to alcohols, from

the tank to the end of the fuel delivery system.

Chemistry 101

The

chemical makeup of alcohol is very corrosive to many of the coatings

that are typically used on metals in the fuel system. It’s not uncommon

for metal components to get surface oxidization and pitting as a result

of alcohol fuels. This becomes a real issue if the alcohol is allowed

to sit in the fuel system between races. The fuel system should be

maintained between races to prevent the alcohol in the system from

turning into what is a very strong corrosive agent.

If

the fuel system isn’t cleaned frequently, preferably after each race

day, the corrosive nature of alcohol will play havoc with the metal and

rubber components in the fuel system, especially those components not

designed for this type of fuel. This isn’t a real issue as most racers

who are using alcohol fuels are already familiar with the required

maintenance. For those not familiar with the maintenance rigors

required when using alcohol fuels; education comes quickly and with a

vengeance.

Butanol

has some unique characteristics; it’s the one alcohol that most closely

mimics gasoline from an energy density perspective. Its stochiometric

air/fuel ratio is the closest to gasoline. Due to its chemical makeup,

butanol isn’t as corrosive as methanol or ethanol. While all of this

sounds great, there are some issues that prevent butanol from being a

viable racing fuel at this point in time. First, is that it has a

fairly high melting point and at cooler room temperatures more closely

resembles Vaseline than a liquid fuel. However, it does mix well with

gasoline and that has some real positives for the passenger car world;

however it’s not a real boon to the racing world, yet. At this time we

will still focus our attention on methanol, while ethanol is gaining

more acceptance.

Failure to properly

maintain an alcohol fuel system will result in, aside from the

corrosion, a grit like substance, almost a fine sand type of residue,

in the lines and around aluminum parts. This grit is the result of an

increased electrical conductivity that alcohol has over gasoline fuels.

The grit is from the galvanic corrosion caused by the greater

electrical conductivity from the fuel as it interacts with the various

different metals in the fuel system. This contamination will migrate

throughout the system clogging fuel filters, fuel jets, and generally

cause havoc within the fuel system.

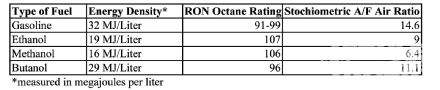

It’s

often thought that alcohol makes power because it has a greater amount

of energy. This isn’t exactly true; in fact, the type of alcohols that

are commonly used in racing have less heat energy than gasoline based

on the volume. There are, in fact, four types of alcohols of which only

methanol and ethanol are currently used as fuels in the racing world.

The other two types of alcohols, propanol and butanol, aren’t used

commonly used. Propanol has more uses as an industrial solvent than as

a fuel while Butanol is an interesting chemical.

More Power

So,

just why does alcohol make more power than gasoline if it has less

energy per pound than gasoline? Good question! Obviously, you will have

to run more of the alcohol-based fuels to get the same power, how much

more will depend on the type of alcohol you’re running. With methanol

and ethanol it’s about 40 percent more than gasoline. Let me espouse

some of the good characteristics that alcohol brings to the table.

First,

when you burn alcohol one of the byproducts of combustion is oxygen.

This helps enhance the combustion process. Another is the cooling

effect of alcohol as it “vaporizes” in the inlet track. This helps

create denser air as the air/fuel charge enters the engine, another

positive. The cooling effect also helps to cool the engine, at least on

the inlet side of the equation. Remember, producing horsepower is all

about creating and controlling heat.

Another

positive feature about alcohol that is seldom discussed is that the

incoming fuel charge, the mixture of air and alcohol, is easier to

compress than a mixture of gasoline and air. The alcohol doesn’t

vaporize as well or as completely as gasoline as it comes out of the

carburetor or the injector. While gasoline forms a more complete vapor,

alcohol forms a “vapor” made up of many very small droplets of fuel

suspended in the incoming air/fuel stream entering the engine. Then

during the compression stroke, the heat of simply compressing the

incoming air/fuel mixture completes the vaporization process.

So,

from a mechanical perspective, your engine uses a smaller percentage of

the power it’s making to sustain continued operation. Long story short,

an alcohol mixture takes less energy to compress than a gasoline

mixture. And, as an added bonus the last vaporization step also helps

to further cool the mixture. Remember, cool, in this case, is a

relative term as compared to a gasoline mixture.

Additionally,

an engine that is burning methanol or ethanol can support a much higher

compression ratio. It’s not uncommon to see alcohol engines using as

high as 13:1 or 14:1 compression rations with little fuel-related

problems. Of course, high compression engines have other mechanical

issues that aren’t related to fuel. That said, alcohol can support some

very high compression engines without the fuel causing detonation

issues which can occur if the wrong grade of gasoline is used.

|